How can an object persist but change? And WTF are time worms?

The problem of temporary intrinsics and where David Lewis went wrong– Anna Ord

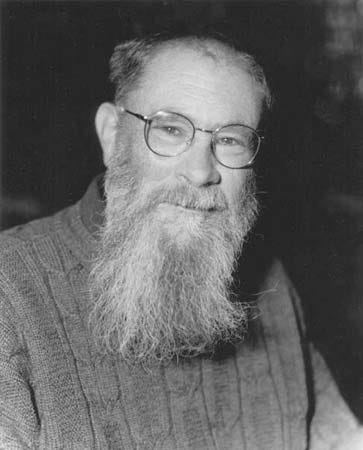

Ordinary objects persist– they exist at more than one time.1 They also seem to change their properties– my cup of coffee was hot one hour ago and is cold now, but it’s true that it’s the same coffee, right? Here’s another idea that we think must be true: ‘if x and y are one and the same, x and y have identical properties’. The problem is, these ideas directly contradict each-other. How can an object persist as one and the same but change its properties, if to be the same it must be identical? To be specific, how can its intrinsic properties– properties that an object has independent of anything else, e.g. the temperature of my coffee, as opposed to extrinsic properties which depend on the object’s relationship with other things– change? This is the problem of temporary intrinsics as proposed by all-around icon David Lewis in 1986.2

The options

Thankfully, the philosophers have been working hard to settle this problem for the last few decades, and (roughly) three camps of theories have emerged. Firstly, we have the endurantists, who think objects persist by being wholly present at more than one time. Inside this faction, the most substantive endurance theory is the relations-to-times view: intrinsic properties are relations that objects endure bearing to times.3 My coffee bears the relation ‘being hot at’ to one hour ago and ‘being cold at’ to now. The coffee is wholly present one hour ago and now.4 However, Lewis thought this idea was, essentially, pretty shite. Obviously properties are not relations! The temperature of my coffee, its mass, and its colour are not relative or dependent on the existence of anything else. Another option is presentism: only the present exists, so no objects exist at times other than the present. Under this view, my coffee is cold in the present, and there is no hot coffee one hour ago. Similarly, this is a pretty terrible stance if we care about intuition and talking about literally anything, so I’m not going to consider this view in this piece. It’s not looking good. Alas, Lewis proposes one of the most influential ideas in philosophy: worm theory, a.k.a. perdurantism. He says ordinary objects perdure through time– they have different temporal parts at different times, with no one part wholly present at more than one time.5 My coffee, for example, is made up of temporal parts and its temporary intrinsics like its temperature are properties of these parts, wherein they differ from one another.6 The coffee’s temporal part one hour ago is hot and its current temporal part is cold. Objects are time-worms– they spread across multiple time slices, instead of the whole thing being present one minute ago and then wholly present again now.

The philosophers have lapped it up, including me. I love David Lewis, and worm theory is an incredibly important theory. Stupid endurantists, their tiny brains just don’t understand that all objects are clearly worms. Case closed. Or is it?

I’m not convinced that Lewis’ argument for outright rejecting endurantism, then accepting perdurantism by default, is sound. In fact, there is one big false assertion. In the rest of this article I’ll explain Lewis’ argument more, propose my problem, then evaluate two perdurantist responses. I think that neither of them stand, and Lewis’ argument, on this very specific point, is unsound.

The criticism

Here is Lewis’ argument from temporary intrinsics again:

P1: Ordinary objects persist but change their intrinsic properties.

P2: Either intrinsic properties are relations to times, objects only exist in the present, or objects perdure.

P3: It is not the case that intrinsic properties are relations to times.

P4: It is not the case that only the present exists.

----------

C: Ordinary objects perdure.7

Lewis is famous for his rapid-fire writing– his argument for worm theory only really occurs over two pages. But all he really has to say about premise three, why intrinsic properties are not relations to times, is:

“If we know what shape is, we know that it is a property, not a relation.”8

Is this a good reason? He thinks endurantism is clearly wrong because objects have intrinsic properties simpliciter, i.e., without relation to anything else, and he thinks this is an intuitive idea. But he doesn’t actually provide a reason for this aside from his own intuition, and I think this is a mistake for perdurantism. If I didn’t love talking about worms so much it would probably be a fatal one. My first issue is that, even if we accept properties like temperature are intrinsic, Lewis has not proven that they are not relations to times, and he really needs to.9 My coffee being hot independent of other objects does not entail it was hot independent of time! My second issue is that perdurantism can also not claim intrinsic properties are had simpliciter– I buy into what Sally Haslanger has to say here.10 The perdurantist relativises objects to times, rather than properties to times like the endurantist (such that for O to be F at t is for O, at t, to have atemporally the property F).11 So, perdurantism can claim that properties like temperature are intrinsic, however, there is no reason for an object to persist through a change in its intrinsic properties.12 The temperature of my perduring coffee at different temporal stages are not properties simpliciter of the coffee. The properties of a perduring object involve a relation between itself and the temporal part. In essence, perdurantism and endurantism are both incompatible with objects having properties simpliciter, so this is not a reason to abandon endurantism and accept Lewis’ assertion.13

Say I want to agree with Lewis and I am desperately committed to the idea that it is unintuitive for objects not to have properties simpliciter. Let’s restrict the domain and consider the properties of my coffee at only time, t, one hour ago, and ignore other times. My coffee bears the relation ‘being hot at’ to t. T is every time the coffee exists as we have restricted the domain, so the coffee is hot simpliciter. So, the endurantist has a fix; they can account for objects having intrinsic properties simpliciter.14 Still, I’m not convinced that an object having properties simpliciter is necessary. Here’s an example: many philosophers claim objects do not have a colour simpliciter, but the colour is relative to a perspective. My coffee mug looks pink to me but a lot of philosophers think that this colour isn’t independent of me. Applying Lewis’ argument, this is a rubbish idea because colours are clearly properties and not relations. But it’s not evident that colours are clearly not relations! Nor is it evident that properties are clearly not relations to times.15 All this is to say, it is certainly not obvious why properties are not relations to times. In fact, the enduranist can provide a pretty solid explanation.

The flip-side

Ted Sider levels a second objection against endurantism that involves problems with talk about parthood. One benefit of endurantism is how it presents objects as wholly present in a moment– all the parts of my coffee up were wholly present one hour ago and wholly present now. For the relations-to-times endurantism, this parthood is a triadic relation between a whole, a part, and a time. Parthood is time-relative.16 However, if I define being wholly present as ‘every part of object x exists at time t’, there is a temporal quantifier missing.17 So how could the endurantist define wholly present? One option is to say something like: “an object is wholly present if necessarily, for every x and every time t at which x exists, everything that is a part of x at some time or other is part of x exists and is a part of x at t”.18 This seems okay and it includes the temporal quantifier. But if we apply this to something like my coffee cup, we get: ‘if the lid is a part of the coffee cup, at every time the cup exists the lid is present’. But this is false! If I take the lid off, I would like to say that the cup has lost a part. That definition isn’t going to work because we need to be able to allow parts to change. Option two is to define wholly present in a weaker way: “necessarily, for every x and every t at which x exists, every part of x at t exists at t”.19 If we substitute in an example again, we get: ‘if at time t the lid is a part of my coffee cup then the lid is present at time t’. Hold on, this seems to be saying nothing! And it is even less helpful for illustrating the disagreement between endurantists and perdurantists over an object being wholly present.20 Sider goes on to propose various definitions, none of which are appropriate. In fact, to explain how an object can change parts, he argues the endurantist is unable to speak atemporally about parts, i.e., what parts an object has, period, not relative to a time and all that stuff. This is not good news. The ability to speak about an object’s parts is an essential criterion for a theory about the nature of persisting objects.21 If the endurantist can’t do this this gives us a reason to side with Lewis.

What if we couldn’t talk about parts atemporally, and that was just… fine? Katherine Hawley has this view. In the same way that it only makes sense for me to speak of the temperature of my coffee in a relative way– “my cup of coffee is hotter than my glass of water”– she says it only makes sense to talk about the part of a persisting object in a way that is relative to time.22 Atemporal talk is helpful but not essential for the endurantist. Sider’s objection on the definition of ‘wholly present’ is also avoided– I can speak of the lid of my coffee cup being a part of it, relative to a time. None of those complicated definitions. If we accept that we just have to talk about parts relative to a time, the relations-to-times version of endurantism holds.

The wild card! (and conclusion)

Whilst I find this response convincing, the enduranists have a final trick up their sleeve. The relations-to-times is the most coherent and explanatory endurantist view, but it’s not the only one. Another option is adverbialism, which does exactly what it says on the tin. Under this view, the temperature of my coffee is a property, not a relation to time, but obtains at different times, say hot at t1, one hour ago. In the same way I might write this article quick-ly, my coffee is hot in a t1-ly way, then cold in a t2-ly way, like an adverb. An object O’s having property F stands temporally in the relation of obtaining at time t.23 As adverbialism modifies the ‘having’ of a property and not the property as it obtains to a time, we get to say the object is one and the same too because the intrinsic properties are shared.24 It evades Sider’s objection because it does not involve the triadic relation between a whole, a part, and a time as with the relations-to-times endurantism. And it even sidesteps Lewis’ rejection of properties as relations to times– properties are just obtained at different times.25 Sider and Lewis are dealt with, we can make sense of objects being one and the same even through change, and it also has a cool name.

The thing is, we only need to move to adverbialism if we really want to think properties aren’t relations to times. Haslanger says this herself.26 It’s also pretty unintuitive and has problems of its own (a story for another article). I think I’ve presented a fair few arguments for why we shouldn’t abandon the relations-to-times accounts, and if you really want to, you might as well go for perdurantism at that point!

My goal in this article was to present a few solutions to the problem of temporary intrinsics, and inside of this, to question Lewis’s dismissal of endurantism. I hope I’ve explained the debate between the endurantists and the perdurantists, and whilst perdurantism does have a lot of merits in other applications, in the argument from temporary intrinsics Lewis has just not presented convincing reasons to reject the idea properties are relations-to-times account. He might as well have said ‘properties are not relations to times… because I said so’. In my eyes the argument from temporary intrinsics for perdurantism just does not hold. Maybe it works in a possible world?

– Anna Ord

For more from Anna, visit Anna– Dream House.

David Lewis, On the Plurality of Worlds (Blackwell, 1986), p. 202.

Ibid., p. 203.

Katherine Hawley, How Things Persist (Clarendon, 2004), p. 16.

Ibid., p. 15.

Lewis, 1986, p. 204.

Ibid.

Ibid., pp. 203-204.

Ibid., p. 204.

Hawley, 2004, p. 21.

Sally Haslanger, “Endurance and Temporary Intrinsics”, Analysis, vol. 49, no. 3 (1989), p. 119.

Hawley, 2004, p. 21.

Haslanger, 1989, p. 119.

Ryan Wasserman, “The Argument from Temporary Intrinsics”, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol. 81, no. 3 (2003), p. 417.

Ibid., p. 418.

Hawley, 2004, p. 22.

Ted Sider, “Four Dimensionalism”, Philosophical Review, vol. 106, no. 1 (1997), p. 209.

Ibid., p. 210.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Hawley, 2011, p. 25.

Sider, 1997, p. 213.

Hawley, 2004, p. 26.

Ibid., p. 22.

Haslanger, 1989, p. 122.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 124.